How do you build a nervous system for a planet? A way to sense, interpret, and respond to environmental threats in real-time, on a global scale? That was the core question last week in Frascati, Italy, where I had the honour of contributing to the formation of the Frascati Pathway, the blueprint for a Global Environmental Data Strategy (GEDS). This evolving strategy is set to be presented for endorsement by UN Member States in December 2025 at the United Nations Environment Assembly, a milestone moment for our planet’s data-driven future.

The occasion was the Third High-Level Expert Group Meeting on Big Data, co-convened by the United Nations Science-Policy-Business Forum on the Environment (UN-SPBF) and the Data for Environment Alliance (DEAL). Hosted by the European Space Agency (ESA) and ISPRA (Italy’s environmental protection agency), the gathering brought together leading thinkers from government, tech, academia, finance, and citizen science to shape the foundational frameworks for a transparent, inclusive, and resilient global environmental data ecosystem.

Here are my key observations and lessons from this remarkable convergence of people and purpose.

A clear consensus emerged: a successful GEDS must be built as a “system of systems” grounded in shared standards. Among these, the standards developed by the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) are especially critical, given that environmental data is inherently spatio-temporal. A centralized, monolithic approach won’t work. Instead, we need an open, federated architecture—much like the World Wide Web itself—that ensures different systems can communicate and interoperate without being controlled by any single entity. These standards must cover different layers from technical data formats to governance protocols and ethical procedures.

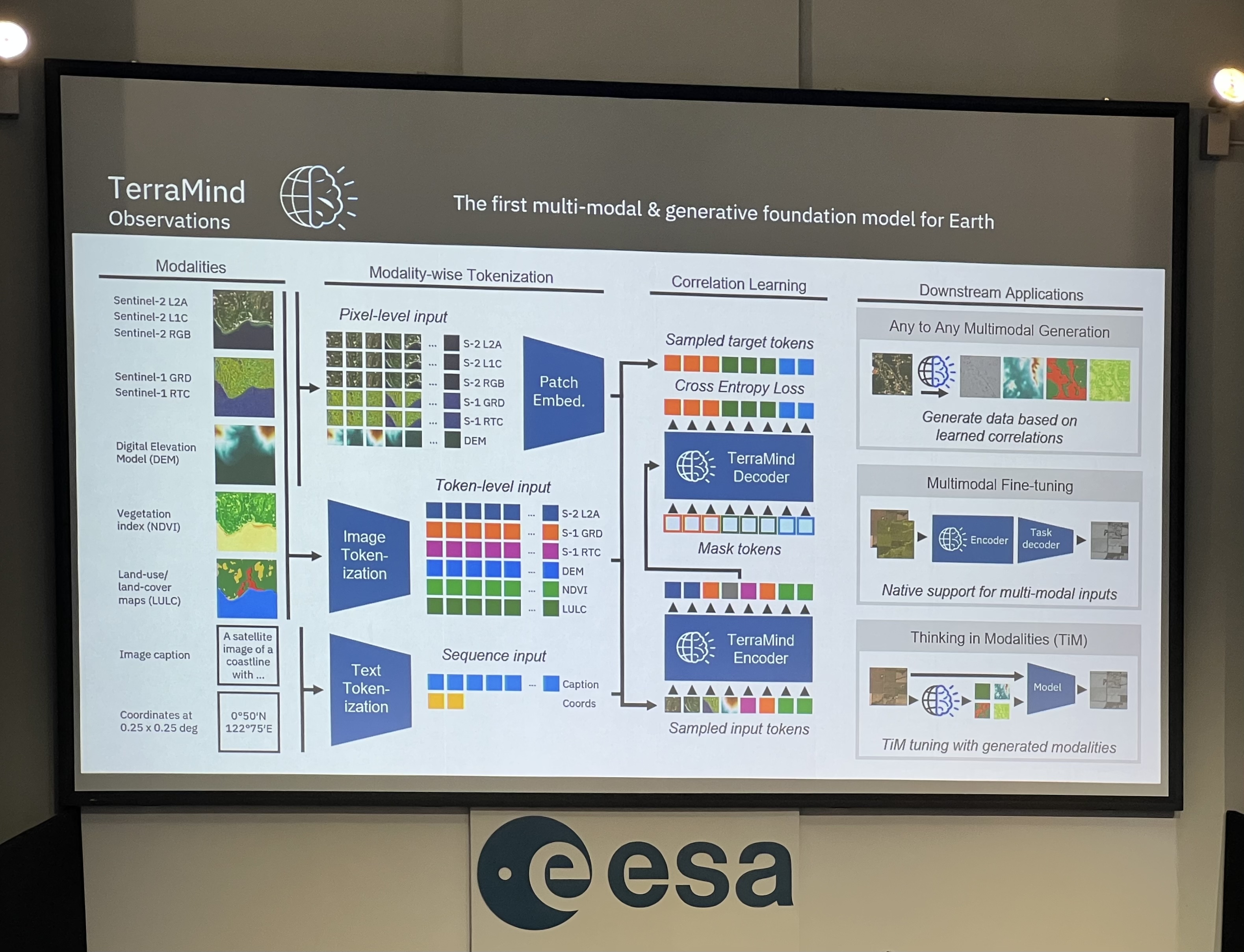

As expected, AI was a central theme. The conversation has clearly shifted from “if” we should use AI to “how” we can deploy it responsibly. For example, IBM’s Chief Data Scientist, Robert Parkin, presented TerraMind, a geospatial foundation model capable of analyzing multi-modal Earth observation data to support diverse applications such as land use monitoring, environmental risk assessment, and infrastructure change detection. It was a powerful demonstration of how AI can move from simply observing environmental change to proactively forecasting it. This underscored the growing consensus that developing geospatial foundation models requires adherence to rigorous data standards—such as those defined by OGC and ISO—for training data quality and interoperability. Furthermore, their generative capabilities must be constrained and contextualized through high-level ontologies to ensure semantic grounding and alignment with environmental science objectives, preventing arbitrary or unstructured outputs.

Both Will Cadel from SparkGeo and I emphasized the need to move beyond raw data formats. Earth observation and sensor networks generate immense volumes of data, but what’s often missing are domain-specific ontologies—essentially, a shared conceptual models that translates raw data into meaningful concepts. For instance, the OGC Emission Event Modeling Language doesn’t just describe a sensor reading; it contextualizes where, when, how, how much, and why an emission event occurred. This high-level modeling is essential if we want to support real analytics and decision-making at scale.

Methane reduction was repeatedly highlighted as a compelling and practical use case. It showcases what’s possible when diverse stakeholders — industry, regulators, satellite operators, AI developers, and a multi-sensor operating platform like SensorUp — collaborate effectively. This is more than just a tech success story; it’s a demonstration of validated business cases and a thriving innovation ecosystem. It demonstrated a simple fact: it just makes sense, economically and environmentally, to keep methane in the pipe. We need more examples like this to inspire and inform the GEDS ecosystem.

One of the most insightful discussions centered on treating uncertainty not as a flaw to be eliminated, but as a core piece of information.

Uncertainty is not a bug, but a feature of working with complex, dynamic environmental systems.

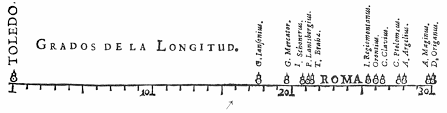

Rather than hiding or oversimplifying it, we must embrace, quantify, and communicate uncertainty as a fundamental element of any decision-support system. One speaker beautifully illustrated this by referencing Van Langren’s 1644 research on the wide range of longitude estimates between Toledo and Rome. The historical example was a powerful reminder that we have always worked with imperfect data. Designing systems that transparently acknowledge uncertainty strengthens trust and enables more resilient decisions.

Resilience came up repeatedly, not just for technical systems, but for funding models, governance, and geopolitics. A truly global environmental data strategy cannot have single points of failure. Recent geopolitical events and elections underscore the risks of overcentralization, reminding us that institutional resilience is just as critical as technical redundancy.

One of my most humbling takeaways was realizing how much of my thinking is shaped by a highly technical, developed-world perspective. A GEDS must reflect diverse viewpoints—not just from different sectors, but from different parts of the world, especially developing nations that contribute vast and often under-acknowledged data. In this era of foundation models hungry for training data, ensuring equitable participation and recognition is not just a nice-to-have—it’s essential. This meeting was a powerful challenge to broaden our collective lens.

Leaving Frascati, I felt deeply inspired. The road ahead is complex, filled with technical hurdles, funding constraints, and political sensitivities. But the shared energy in the room made one thing clear: the world is ready for a Global Environmental Data Strategy built on standards, inclusion, and collaboration. This is one of those rare moments when you feel the right people, ideas, and timing have finally come together.

The world is, indeed, a positive place. Especially when we choose to build it together. #BetterTogether