Over the last decade, methane monitoring has advanced rapidly. Satellites now provide global coverage, aircraft campaigns deliver high-resolution measurements, continuous monitoring systems operate at facilities, and reporting frameworks continue to mature.

Yet despite this progress, methane mitigation efforts still struggle to scale. The limiting factor is no longer sensing. It is data management.

More specifically, it is the absence of a standard spatial foundation for organizing, aggregating, and reasoning over methane emissions data.

In 2026, we published a peer-reviewed journal paper in the International Journal of Digital Earth, titled “Enabling a Digital Earth for methane emissions management with equal-area discrete global grids” (Li and Liang, 2026), which focuses on one core idea:

Without a standardized notion of “space,” methane data cannot be managed consistently, compared fairly, or used reliably for analytics and AI.

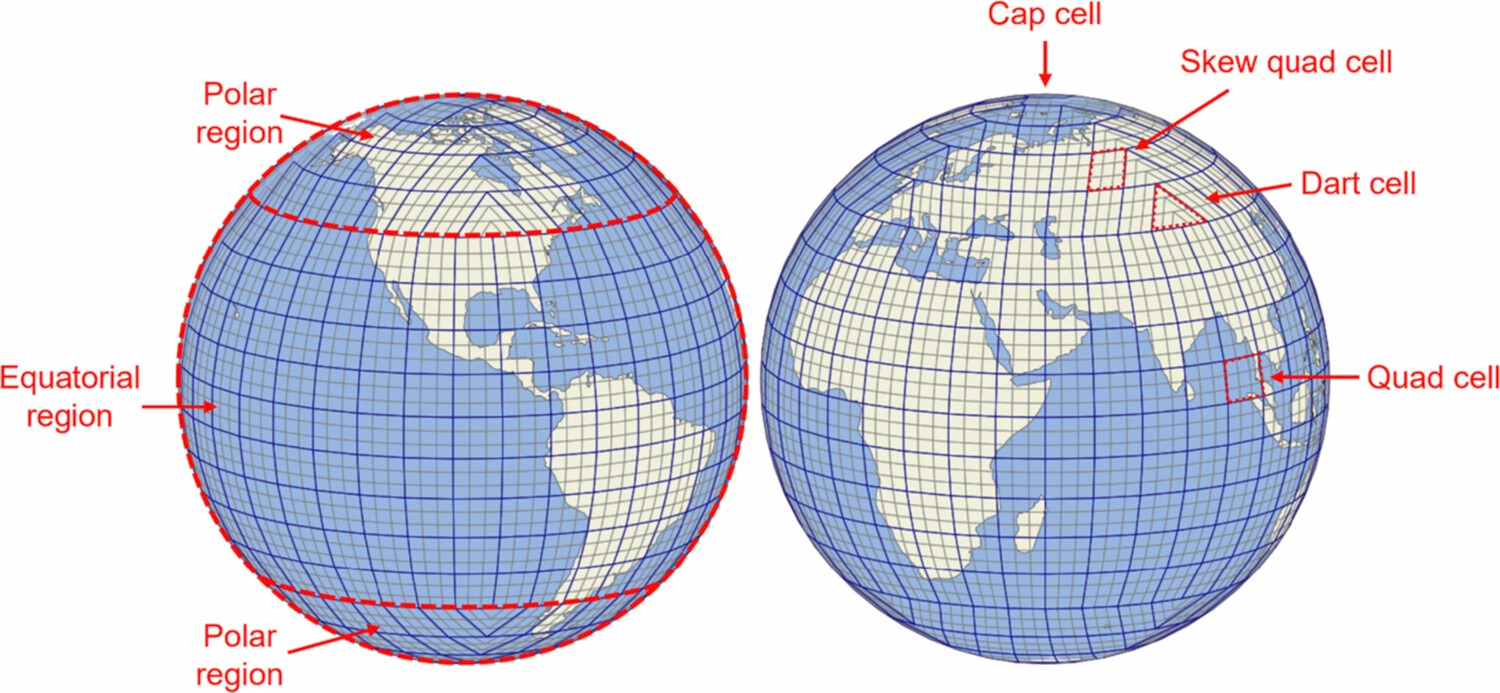

Figure 1. We propose a rHEALPix DGGS for emissions data management. The figure illustrates cell structures in the polar and equatorial regions of rHEALPix (𝑁𝑠𝑖𝑑𝑒=3) at resolution levels 2 and 3. (Li and Liang, 2026)

A robust methane data infrastructure requires standardization across at least three dimensions:

These dimensions are tightly bound. However, space is foundational. If spatial units are unstable, inconsistent, or biased, everything built on top of them inherits those problems.

This peer-reviewed research focuses on space, not because time and semantics are less important, but because spatial standardization is a prerequisite for getting the others right. Our work on the OGC Emission Event Modeling Language (EmissionML) addresses the challenges of semantics and data lineage. Interested readers can find more information on the OGC EmissionML GitHub.

Most methane inventories, maps, and analytics pipelines rely—explicitly or implicitly—on latitude–longitude grids. These grids are convenient, widely supported, and deeply ingrained in geospatial tooling.

They also introduce a fundamental problem:

The latitude–longitude grid cells do not represent equal areas.

As latitude increases, grid cells shrink. This has several consequences that are often underestimated:

These issues are manageable in small, single-purpose analyses. They become serious liabilities when methane data must support:

At that point, spatial inconsistency becomes technical debt.

An alternative exists: equal-area, hierarchical spatial grids, commonly referred to as Discrete Global Grid Systems (DGGS). In our research paper, we proposed an equal-area, hierarchical spatial fabric (DGGS / rHEALPix) for emissions data.

The key properties are simple but powerful:

Together, these properties transform spatial data from something that is drawn into something that is operated on.

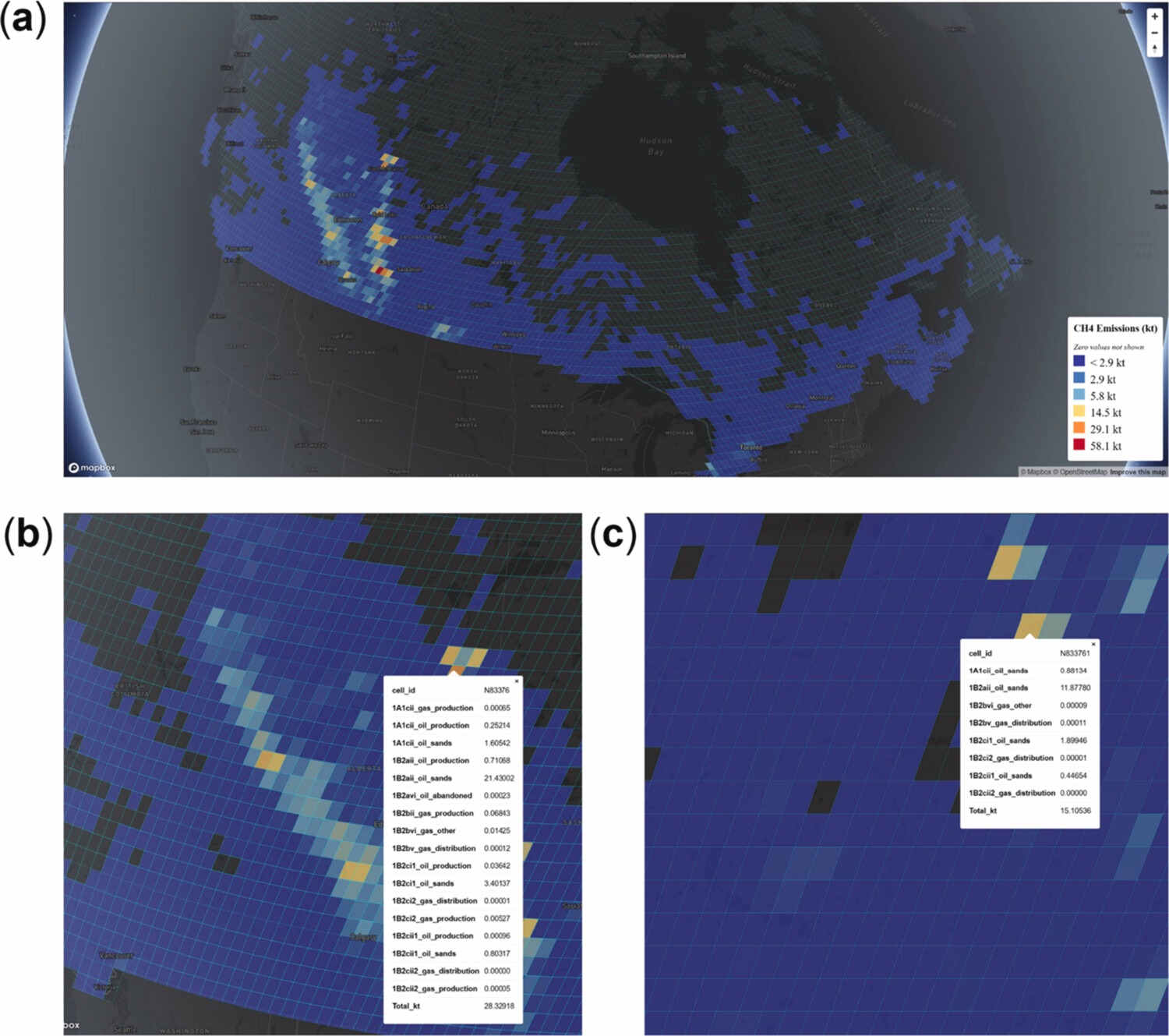

Figure 2. Visualisation of the 2018 oil and gas methane emissions from Scarpelli, Jacob, Moran, et al., converted to the rHEALPix DGGS. (a) Overview of emissions at resolution 5; (b) grid-level emissions for cell “N83376” near Fort McMurray at resolution 5; (c) resolution 6 view for cell “N833761” at the same location.

From an operational perspective, spatial standardization enables several capabilities that are otherwise difficult to achieve:

Spatial standardization becomes even more critical when methane data is used for AI and advanced analytics.

AI systems depend on stable, discrete representations. They struggle when spatial units:

A standardized, equal-area, hierarchical spatial framework provides:

In other words, AI needs a spatial unit of record.

Without it, models may still produce outputs—but those outputs are more complex to interpret, reproduce, and trust.

Defining a spatial standard is necessary, but not sufficient. Standards must be operationalized.

At SensorUp, our work sits at the intersection of standards, data infrastructure, and operational systems. We see standardized spatial foundations not as abstract theory, but as enabling infrastructure that makes methane data:

This is where research, standards development, and platform engineering meet.

A spatial standard only creates value when it is:

This journal paper focuses on space. Time and semantics matter equally, and they must ultimately be addressed together.

We are currently extending this work to show how standardized spatial foundations can be used to ground generative AI systems, improving the credibility, reproducibility, and traceability of AI-driven methane analytics. That research is undergoing peer review; please stay tuned.

The broader message is simple:

“Methane mitigation will not scale without data standardization.

And data standardization must start with space.”

For organizations interested in transitioning from detection to durable methane operations—and in translating standards into practical systems—we welcome collaboration.

By partnering with SensorUp, you can help define, implement, and operationalize the next-generation data infrastructure.